Human Biology does nothing to structure human society. Age may enfeeble us all, but cultures vary considerably in the prestige and power they accord to the elderly. Giving birth is a necessary condition for being a mother, but it is not sufficient. We expect mothers to behave in maternal ways and to display appropriately maternal sentiments. We prescribe a clutch of norms or rules that govern the role of a mother. That the social role is independent of the biological base can be demonstrated by going back three sentences. Giving birth is certainly not sufficient to be a mother but, as adoption and fostering show, it is not even necessary!

The fine detail of what is expected of a mother or a father or a dutiful son differs from culture to culture, but everywhere behaviour is coordinated by the reciprocal nature of roles. Husbands and wives, parents and children, employers and employees, waiters and customers, teachers and pupils, warlords and followers; each makes sense only in its relation to the other. The term ‘role’ is an appropriate one, because the metaphor of an actor in a play neatly expresses the rule-governed nature or scripted nature of much of social life and the sense that society is a joint production. Social life occurs only because people play their parts (and that is as true for war and conflicts as for peace and love) and those parts make sense only in the context of the overall show. The drama metaphor also reminds us of the artistic licence available to the players. We can play a part straight or, as the following from J.P. Sartre conveys, we can ham it up.

Let us consider this waiter in the cafe. His movement is quick and forward, a little too precise, a little too rapid. He comes towards the patrons with a step a little too quick. He bends forward a little too eagerly; his voice, his eyes express an interest a little too solicitous for the order of the customer. Finally there he returns, trying to imitate in his walk the inflexible stiffness of some kind of automaton while carrying his tray with the recklessness of a tightrope-walker...All his behaviour seems to us a game...But what is he playing? We need not watch long before we can explain it: he is playing at being a waiter in a cafe.

The American sociologist Erving Goffman built an influential body of social analysis on elaborations of the metaphor of social life as drama. Perhaps his most telling point was that it is only through acting out a part that we express character. It is not enough to be evil or virtuous; we have to be seen to be evil or virtuous. There is distinction between the roles we play and some underlying self. Here we might note that some roles are more absorbing than others. We would not be surprised by the waitress who plays the part in such a way as to signal to us that she is much more than her occupation. We would be surprised and offended by the father who played his part ‘tongue in cheek’. Some roles are broader and more far-reaching than others. Describing someone as a clergyman or faith healer would say far more about that person than describing someone as a bus driver.

Human Biology does nothing to structure human society. Age may enfeeble us all, but cultures vary considerably in the prestige and power they accord to the elderly. Giving birth is a necessary condition for being a mother, but it is not sufficient. We expect mothers to behave in maternal ways and to display appropriately maternal sentiments. We prescribe a clutch of norms or rules that govern the role of a mother. That the social role is independent of the biological base can be demonstrated by going back three sentences. Giving birth is certainly not sufficient to be a mother but, as adoption and fostering show, it is not even necessary!

The fine detail of what is expected of a mother or a father or a dutiful son differs from culture to culture, but everywhere behaviour is coordinated by the reciprocal nature of roles. Husbands and wives, parents and children, employers and employees, waiters and customers, teachers and pupils, warlords and followers; each makes sense only in its relation to the other. The term ‘role’ is an appropriate one, because the metaphor of an actor in a play neatly expresses the rule-governed nature or scripted nature of much of social life and the sense that society is a joint production. Social life occurs only because people play their parts (and that is as true for war and conflicts as for peace and love) and those parts make sense only in the context of the overall show. The drama metaphor also reminds us of the artistic licence available to the players. We can play a part straight or, as the following from J.P. Sartre conveys, we can ham it up.

Let us consider this waiter in the cafe. His movement is quick and forward, a little too precise, a little too rapid. He comes towards the patrons with a step a little too quick. He bends forward a little too eagerly; his voice, his eyes express an interest a little too solicitous for the order of the customer. Finally there he returns, trying to imitate in his walk the inflexible stiffness of some kind of automaton while carrying his tray with the recklessness of a tightrope-walker...All his behaviour seems to us a game...But what is he playing? We need not watch long before we can explain it: he is playing at being a waiter in a cafe.

The American sociologist Erving Goffman built an influential body of social analysis on elaborations of the metaphor of social life as drama. Perhaps his most telling point was that it is only through acting out a part that we express character. It is not enough to be evil or virtuous; we have to be seen to be evil or virtuous. There is distinction between the roles we play and some underlying self. Here we might note that some roles are more absorbing than others. We would not be surprised by the waitress who plays the part in such a way as to signal to us that she is much more than her occupation. We would be surprised and offended by the father who played his part ‘tongue in cheek’. Some roles are broader and more far-reaching than others. Describing someone as a clergyman or faith healer would say far more about that person than describing someone as a bus driver.

Human Biology does nothing to structure human society. Age may enfeeble us all, but cultures vary considerably in the prestige and power they accord to the elderly. Giving birth is a necessary condition for being a mother, but it is not sufficient. We expect mothers to behave in maternal ways and to display appropriately maternal sentiments. We prescribe a clutch of norms or rules that govern the role of a mother. That the social role is independent of the biological base can be demonstrated by going back three sentences. Giving birth is certainly not sufficient to be a mother but, as adoption and fostering show, it is not even necessary!

The fine detail of what is expected of a mother or a father or a dutiful son differs from culture to culture, but everywhere behaviour is coordinated by the reciprocal nature of roles. Husbands and wives, parents and children, employers and employees, waiters and customers, teachers and pupils, warlords and followers; each makes sense only in its relation to the other. The term ‘role’ is an appropriate one, because the metaphor of an actor in a play neatly expresses the rule-governed nature or scripted nature of much of social life and the sense that society is a joint production. Social life occurs only because people play their parts (and that is as true for war and conflicts as for peace and love) and those parts make sense only in the context of the overall show. The drama metaphor also reminds us of the artistic licence available to the players. We can play a part straight or, as the following from J.P. Sartre conveys, we can ham it up.

Let us consider this waiter in the cafe. His movement is quick and forward, a little too precise, a little too rapid. He comes towards the patrons with a step a little too quick. He bends forward a little too eagerly; his voice, his eyes express an interest a little too solicitous for the order of the customer. Finally there he returns, trying to imitate in his walk the inflexible stiffness of some kind of automaton while carrying his tray with the recklessness of a tightrope-walker...All his behaviour seems to us a game...But what is he playing? We need not watch long before we can explain it: he is playing at being a waiter in a cafe.

The American sociologist Erving Goffman built an influential body of social analysis on elaborations of the metaphor of social life as drama. Perhaps his most telling point was that it is only through acting out a part that we express character. It is not enough to be evil or virtuous; we have to be seen to be evil or virtuous. There is distinction between the roles we play and some underlying self. Here we might note that some roles are more absorbing than others. We would not be surprised by the waitress who plays the part in such a way as to signal to us that she is much more than her occupation. We would be surprised and offended by the father who played his part ‘tongue in cheek’. Some roles are broader and more far-reaching than others. Describing someone as a clergyman or faith healer would say far more about that person than describing someone as a bus driver.

DIRECTIONS for the following three questions:

In each question, there are five sentences or parts of sentences that form a paragraph. Identify the sentence(s) or part(s) of sentence(s) that is/are correct in terms of grammar and usage. Then, choose the most appropriate option.

There are five sentences or parts of sentences that form a paragraph. Identify the sentence(s) or part(s) of sentence(s) that is/are correct in terms of grammar and usage. Then, choose the most appropriate option.

DIRECTIONS for the following three questions:

In each question, there are five sentences or parts of sentences that form a paragraph. Identify the sentence(s) or part(s) of sentence(s) that is/are correct in terms of grammar and usage. Then, choose the most appropriate option.

Every civilized society lives and thrives on a silent but profound agreement as to what is to be accepted as the valid mould of experience. Civilization is a complex system of dams, dykes, and canals warding off, directing, and articulating the influx of the surrounding fluid element; a fertile fenland, elaborately drained and protected from the high tides of chaotic, unexercised, and inarticulate experience. In such a culture, stable and sure of itself within the frontiers of 'naturalized' experience, the arts wield their creative power not so much in width as in-depth. They do not create new experience, but deepen and purify the old. Their works do not differ from one another like a new horizon from a new horizon, but like a madonna from a madonna.

The periods of art which are most vigorous in creative passion seem to occur when the established pattern of experience loosens its rigidity without as yet losing its force. Such a period was the Renaissance, and Shakespeare its poetic consummation. Then it was as though the discipline of the old order gave depth to the excitement of the breaking away, the depth of job and tragedy, of incomparable conquests and irredeemable losses. Adventurers of experience set out as though in lifeboats to rescue and bring back to the shore treasures of knowing and feeling which the old order had left floating on the high seas. The works of the early Renaissance and the poetry of Shakespeare vibrate with the compassion for live experience in danger of dying from exposure and neglect. In this compassion was the creative genius of the age. Yet, it was a genius of courage, not of desperate audacity. For, however elusively, it still knew of harbours and anchors, of homes to which to return, and of barns in which to store the harvest. The exploring spirit of art was in the depths of its consciousness still aware of a scheme of things into which to fit its exploits and creations.

But the more this scheme of things loses its stability, the more boundless and uncharted appears the ocean of potential exploration. In the blank confusion of infinite potentialities flotsam of significance gets attached to jetsam of experience; for everything is sea, everything is at sea - ....

The sea is all about us;

The sea is the land's edge also, the granite

Into which it reaches, the beaches where it tosses

Its hints of earlier and other creation ...

- and Rilke tells a story in which, as in T.S. Eliot's poem, it is again the sea and the distance of 'other creation' that becomes the image of the poet's reality. A rowing boat sets out on a difficult passage. The oarsmen labour in exact rhythm. There is no sign yet of the destination. Suddenly a man, seemingly idle, breaks out into song. And if the labour of the oarsmen meaninglessly defeats the real resistance of the real waves, it is the idle single who magically conquers the despair of apparent aimlessness. While the people next to him try to come to grips with the element that is next to them, his voice seems to bind the boat to the farthest distance so that the farthest distance draws it towards itself. 'I don't know why and how,' is Rilke's conclusion, 'but suddenly I understood the situation of the poet, his place and function in this age. It does not matter if one denies him every place - except this one. There one must tolerate him.'

Every civilized society lives and thrives on a silent but profound agreement as to what is to be accepted as the valid mould of experience. Civilization is a complex system of dams, dykes, and canals warding off, directing, and articulating the influx of the surrounding fluid element; a fertile fenland, elaborately drained and protected from the high tides of chaotic, unexercised, and inarticulate experience. In such a culture, stable and sure of itself within the frontiers of 'naturalized' experience, the arts wield their creative power not so much in width as in-depth. They do not create new experience, but deepen and purify the old. Their works do not differ from one another like a new horizon from a new horizon, but like a madonna from a madonna.

The periods of art which are most vigorous in creative passion seem to occur when the established pattern of experience loosens its rigidity without as yet losing its force. Such a period was the Renaissance, and Shakespeare its poetic consummation. Then it was as though the discipline of the old order gave depth to the excitement of the breaking away, the depth of job and tragedy, of incomparable conquests and irredeemable losses. Adventurers of experience set out as though in lifeboats to rescue and bring back to the shore treasures of knowing and feeling which the old order had left floating on the high seas. The works of the early Renaissance and the poetry of Shakespeare vibrate with the compassion for live experience in danger of dying from exposure and neglect. In this compassion was the creative genius of the age. Yet, it was a genius of courage, not of desperate audacity. For, however elusively, it still knew of harbours and anchors, of homes to which to return, and of barns in which to store the harvest. The exploring spirit of art was in the depths of its consciousness still aware of a scheme of things into which to fit its exploits and creations.

But the more this scheme of things loses its stability, the more boundless and uncharted appears the ocean of potential exploration. In the blank confusion of infinite potentialities flotsam of significance gets attached to jetsam of experience; for everything is sea, everything is at sea - ....

The sea is all about us;

The sea is the land's edge also, the granite

Into which it reaches, the beaches where it tosses

Its hints of earlier and other creation ...

- and Rilke tells a story in which, as in T.S. Eliot's poem, it is again the sea and the distance of 'other creation' that becomes the image of the poet's reality. A rowing boat sets out on a difficult passage. The oarsmen labour in exact rhythm. There is no sign yet of the destination. Suddenly a man, seemingly idle, breaks out into song. And if the labour of the oarsmen meaninglessly defeats the real resistance of the real waves, it is the idle single who magically conquers the despair of apparent aimlessness. While the people next to him try to come to grips with the element that is next to them, his voice seems to bind the boat to the farthest distance so that the farthest distance draws it towards itself. 'I don't know why and how,' is Rilke's conclusion, 'but suddenly I understood the situation of the poet, his place and function in this age. It does not matter if one denies him every place - except this one. There one must tolerate him.'

Every civilized society lives and thrives on a silent but profound agreement as to what is to be accepted as the valid mould of experience. Civilization is a complex system of dams, dykes, and canals warding off, directing, and articulating the influx of the surrounding fluid element; a fertile fenland, elaborately drained and protected from the high tides of chaotic, unexercised, and inarticulate experience. In such a culture, stable and sure of itself within the frontiers of 'naturalized' experience, the arts wield their creative power not so much in width as in-depth. They do not create new experience, but deepen and purify the old. Their works do not differ from one another like a new horizon from a new horizon, but like a madonna from a madonna.

The periods of art which are most vigorous in creative passion seem to occur when the established pattern of experience loosens its rigidity without as yet losing its force. Such a period was the Renaissance, and Shakespeare its poetic consummation. Then it was as though the discipline of the old order gave depth to the excitement of the breaking away, the depth of job and tragedy, of incomparable conquests and irredeemable losses. Adventurers of experience set out as though in lifeboats to rescue and bring back to the shore treasures of knowing and feeling which the old order had left floating on the high seas. The works of the early Renaissance and the poetry of Shakespeare vibrate with the compassion for live experience in danger of dying from exposure and neglect. In this compassion was the creative genius of the age. Yet, it was a genius of courage, not of desperate audacity. For, however elusively, it still knew of harbours and anchors, of homes to which to return, and of barns in which to store the harvest. The exploring spirit of art was in the depths of its consciousness still aware of a scheme of things into which to fit its exploits and creations.

But the more this scheme of things loses its stability, the more boundless and uncharted appears the ocean of potential exploration. In the blank confusion of infinite potentialities flotsam of significance gets attached to jetsam of experience; for everything is sea, everything is at sea - ....

The sea is all about us;

The sea is the land's edge also, the granite

Into which it reaches, the beaches where it tosses

Its hints of earlier and other creation ...

- and Rilke tells a story in which, as in T.S. Eliot's poem, it is again the sea and the distance of 'other creation' that becomes the image of the poet's reality. A rowing boat sets out on a difficult passage. The oarsmen labour in exact rhythm. There is no sign yet of the destination. Suddenly a man, seemingly idle, breaks out into song. And if the labour of the oarsmen meaninglessly defeats the real resistance of the real waves, it is the idle single who magically conquers the despair of apparent aimlessness. While the people next to him try to come to grips with the element that is next to them, his voice seems to bind the boat to the farthest distance so that the farthest distance draws it towards itself. 'I don't know why and how,' is Rilke's conclusion, 'but suddenly I understood the situation of the poet, his place and function in this age. It does not matter if one denies him every place - except this one. There one must tolerate him.'

Each of the following questions has a paragraph from which the last sentence has been deleted. From the given options, choose the sentence that completes the paragraph in the most appropriate way.

Each of the following questions has a paragraph from which the last sentence has been deleted. From the given options, choose the sentence that completes the paragraph in the most appropriate way.

Each of the following questions has a paragraph from which the last sentence has been deleted. From the given options, choose the sentence that completes the paragraph in the most appropriate way.

To discover the relation between rules, paradigms, and normal science, consider first how the historian isolates the particular loci of commitment that have been described as accepted rules. Close historical investigation of a given specialty at a given time discloses a set of recurrent and quasi-standard illustrations of various theories in their conceptual, observational, and instrumental applications. These are the community's paradigms, revealed in its textbooks, lectures, and laboratory exercises. By studying them and by practicing with them, the members of the corresponding community learn their trade. The historian, of course, will discover in addition a penumbral area occupied by achievements whose status is still in doubt, but the core of solved problems and techniques will usually be clear. Despite occasional ambiguities, the paradigms of a mature scientific community can be determined with relative

ease.

That demands a second step and one of a somewhat different kind. When undertaking it, the historian must compare the community's paradigms with each other and with its current research reports. In doing so, his object is to discover what isolable elements, explicit or implicit, the members of that community may have abstracted from their more global paradigms and deploy it as rules in their research. Anyone who has attempted to describe or analyze the

evolution of a particular scientific tradition will necessarily have sought accepted principles and rules of this sort. Almost certainly, he will have met with at least partial success. But, if his1 9 experience has been at all like my own, he will have found the search for rules both more difficult and less satisfying than the search for paradigms. Some of the generalizations he employs to describe the community's shared beliefs will present more problems. Others, however,

will seem a shade too strong. Phrased in just that way, or in any other way he can imagine, they would almost certainly have been rejected by some members of the group he studies. Nevertheless, if the coherence of the research tradition is to be understood in terms of rules, some specification of common ground in the corresponding area is needed. As a result, the search for a body of rules competent to constitute a given normal research tradition becomes a source of continual and deep frustration.

Recognizing that frustration, however, makes it possible to diagnose its source. Scientists can agree that a Newton, Lavoisier, Maxwell, or Einstein has produced an apparently permanent solution to a group of outstanding problems and still disagree, sometimes without being aware of it, about the particular abstract characteristics that make those solutions permanent. They can, that is, agree in their identification of a paradigm without agreeing on, or even

attempting to produce, a full interpretation or rationalization of it. Lack of a standard interpretation or of an agreed reduction to rules will not prevent a paradigm from guiding research. Normal science can be determined in part by the direct inspection of paradigms, a process that is often aided by but does not depend upon the formulation of rules and assumption. Indeed, the existence of a paradigm need not even imply that any full set of rules exists.

To discover the relation between rules, paradigms, and normal science, consider first how the historian isolates the particular loci of commitment that have been described as accepted rules. Close historical investigation of a given specialty at a given time discloses a set of recurrent and quasi-standard illustrations of various theories in their conceptual, observational, and instrumental applications. These are the community's paradigms, revealed in its textbooks, lectures, and laboratory exercises. By studying them and by practicing with them, the members of the corresponding community learn their trade. The historian, of course, will discover in addition a penumbral area occupied by achievements whose status is still in doubt, but the core of solved problems and techniques will usually be clear. Despite occasional ambiguities, the paradigms of a mature scientific community can be determined with relative

ease.

That demands a second step and one of a somewhat different kind. When undertaking it, the historian must compare the community's paradigms with each other and with its current research reports. In doing so, his object is to discover what isolable elements, explicit or implicit, the members of that community may have abstracted from their more global paradigms and deploy it as rules in their research. Anyone who has attempted to describe or analyze the

evolution of a particular scientific tradition will necessarily have sought accepted principles and rules of this sort. Almost certainly, he will have met with at least partial success. But, if his1 9 experience has been at all like my own, he will have found the search for rules both more difficult and less satisfying than the search for paradigms. Some of the generalizations he employs to describe the community's shared beliefs will present more problems. Others, however,

will seem a shade too strong. Phrased in just that way, or in any other way he can imagine, they would almost certainly have been rejected by some members of the group he studies. Nevertheless, if the coherence of the research tradition is to be understood in terms of rules, some specification of common ground in the corresponding area is needed. As a result, the search for a body of rules competent to constitute a given normal research tradition becomes a source of continual and deep frustration.

Recognizing that frustration, however, makes it possible to diagnose its source. Scientists can agree that a Newton, Lavoisier, Maxwell, or Einstein has produced an apparently permanent solution to a group of outstanding problems and still disagree, sometimes without being aware of it, about the particular abstract characteristics that make those solutions permanent. They can, that is, agree in their identification of a paradigm without agreeing on, or even

attempting to produce, a full interpretation or rationalization of it. Lack of a standard interpretation or of an agreed reduction to rules will not prevent a paradigm from guiding research. Normal science can be determined in part by the direct inspection of paradigms, a process that is often aided by but does not depend upon the formulation of rules and assumption. Indeed, the existence of a paradigm need not even imply that any full set of rules exists.

To discover the relation between rules, paradigms, and normal science, consider first how the historian isolates the particular loci of commitment that have been described as accepted rules. Close historical investigation of a given specialty at a given time discloses a set of recurrent and quasi-standard illustrations of various theories in their conceptual, observational, and instrumental applications. These are the community's paradigms, revealed in its textbooks, lectures, and laboratory exercises. By studying them and by practicing with them, the members of the corresponding community learn their trade. The historian, of course, will discover in addition a penumbral area occupied by achievements whose status is still in doubt, but the core of solved problems and techniques will usually be clear. Despite occasional ambiguities, the paradigms of a mature scientific community can be determined with relative

ease.

That demands a second step and one of a somewhat different kind. When undertaking it, the historian must compare the community's paradigms with each other and with its current research reports. In doing so, his object is to discover what isolable elements, explicit or implicit, the members of that community may have abstracted from their more global paradigms and deploy it as rules in their research. Anyone who has attempted to describe or analyze the

evolution of a particular scientific tradition will necessarily have sought accepted principles and rules of this sort. Almost certainly, he will have met with at least partial success. But, if his1 9 experience has been at all like my own, he will have found the search for rules both more difficult and less satisfying than the search for paradigms. Some of the generalizations he employs to describe the community's shared beliefs will present more problems. Others, however,

will seem a shade too strong. Phrased in just that way, or in any other way he can imagine, they would almost certainly have been rejected by some members of the group he studies. Nevertheless, if the coherence of the research tradition is to be understood in terms of rules, some specification of common ground in the corresponding area is needed. As a result, the search for a body of rules competent to constitute a given normal research tradition becomes a source of continual and deep frustration.

Recognizing that frustration, however, makes it possible to diagnose its source. Scientists can agree that a Newton, Lavoisier, Maxwell, or Einstein has produced an apparently permanent solution to a group of outstanding problems and still disagree, sometimes without being aware of it, about the particular abstract characteristics that make those solutions permanent. They can, that is, agree in their identification of a paradigm without agreeing on, or even

attempting to produce, a full interpretation or rationalization of it. Lack of a standard interpretation or of an agreed reduction to rules will not prevent a paradigm from guiding research. Normal science can be determined in part by the direct inspection of paradigms, a process that is often aided by but does not depend upon the formulation of rules and assumption. Indeed, the existence of a paradigm need not even imply that any full set of rules exists.

There are four sentences. Each sentence has pairs of words/phrases that are italicized and highlighted.

From the italicized and highlighted word(s)/phrase(s), select the most appropriate word(s)/phrase(s) to form correct sentences. Then, from the options given, choose the best one.

There are four sentences. Each sentence has pairs of words/phrases that are italicized and highlighted.

From the italicized and highlighted word(s)/phrase(s), select the most appropriate word(s)/phrase(s) to form correct sentences. Then, from the options given, choose the best one.

There are four sentences. Each sentence has pairs of words/phrases that are italicized and highlighted.

From the italicized and highlighted word(s)/phrase(s), select the most appropriate word(s)/phrase(s) to form correct sentences. Then, from the options given, choose the best one.

The difficulties historians face in establishing cause-and-effect relations in the history of human societies are broadly similar to the difficulties facing astronomers, climatologists, ecologists, evolutionary biologists, geologists, and palaeontologists. To varying degrees each of these fields is plagued by the impossibility of performing replicated, controlled experimental interventions, the complexity arising from enormous numbers of variables, the resulting uniqueness of each system, the consequent impossibility of formulating universal laws, and the difficulties of predicting emergent properties and future behaviour. Prediction in history, as in other historical sciences, is most feasible on large spatial scales and over long times, when the unique features of millions of small-scale brief events become averaged out. Just as I could predict the sex ratio of the next 1,000 newborns but not the sexes of my own two children, the historian can recognize factors that made2 1 inevitable the broad outcome of the collision between American and Eurasian societies after 13,000 years of separate developments, but not the outcome of the 1960 U.S. presidential election. The details of which candidate said what during a single televised debate in October 1960 Could have given the electoral victory to Nixon instead of to Kennedy, but no details of who said what could have blocked the European conquest of Native Americans. How can students of human history profit from the experience of scientists in other historical sciences? A methodology that has proved useful involves the comparative method and so-called natural experiments. While neither astronomers studying galaxy formation nor human historians can manipulate their systems in controlled laboratory experiments, they both can take advantage of natural experiments, by comparing systems differing in the presence or absence (or in the strong or weak effect) of some putative causative factor. For example, epidemiologists, forbidden to feed large amounts of salt to people experimentally, have still been able to identify effects of high salt intake by comparing groups of humans who already differ greatly in their salt intake; and cultural anthropologists, unable to provide human groups experimentally with varying resource abundances for many centuries, still study long-term effects of resource abundance on human societies by comparing recent Polynesian populations living on islands differing naturally in resource abundance.

The student of human history can draw on many more natural experiments than just comparisons among the five inhabited continents. Comparisons can also utilize large islands that have developed complex societies in a considerable degree of isolation (such as Japan, Madagascar, Native American Hispaniola, New Guinea, Hawaii, and many others), as well as societies on hundreds of smaller islands and regional societies within each of the continents. Natural experiments in any field, whether in ecology or human history, are inherently open to potential methodological criticisms. Those include confounding effects of natural variation in additional variables besides the one of interest, as well as problems in inferring chains of causation from observed correlations between variables. Such methodological problems have been discussed in great detail for some of the historical sciences. In particular, epidemiology, the science of drawing inferences about human diseases by comparing groups of people (often by retrospective historical studies), has for a long time successfully employed formalized procedures for dealing with problems similar to those facing historians of human societies. In short, I acknowledge that it is much more difficult to understand human history than to understand problems in fields of science where history is unimportant and where fewer individual variables operate. Nevertheless, successful methodologies for analyzing historical problems have been worked out in several fields. As a result, the histories of dinosaurs, nebulae, and glaciers are generally acknowledged to belong to fields of science rather than to the humanities.

The difficulties historians face in establishing cause-and-effect relations in the history of human societies are broadly similar to the difficulties facing astronomers, climatologists, ecologists, evolutionary biologists, geologists, and palaeontologists. To varying degrees each of these fields is plagued by the impossibility of performing replicated, controlled experimental interventions, the complexity arising from enormous numbers of variables, the resulting uniqueness of each system, the consequent impossibility of formulating universal laws, and the difficulties of predicting emergent properties and future behaviour. Prediction in history, as in other historical sciences, is most feasible on large spatial scales and over long times, when the unique features of millions of small-scale brief events become averaged out. Just as I could predict the sex ratio of the next 1,000 newborns but not the sexes of my own two children, the historian can recognize factors that made2 1 inevitable the broad outcome of the collision between American and Eurasian societies after 13,000 years of separate developments, but not the outcome of the 1960 U.S. presidential election. The details of which candidate said what during a single televised debate in October 1960 Could have given the electoral victory to Nixon instead of to Kennedy, but no details of who said what could have blocked the European conquest of Native Americans. How can students of human history profit from the experience of scientists in other historical sciences? A methodology that has proved useful involves the comparative method and so-called natural experiments. While neither astronomers studying galaxy formation nor human historians can manipulate their systems in controlled laboratory experiments, they both can take advantage of natural experiments, by comparing systems differing in the presence or absence (or in the strong or weak effect) of some putative causative factor. For example, epidemiologists, forbidden to feed large amounts of salt to people experimentally, have still been able to identify effects of high salt intake by comparing groups of humans who already differ greatly in their salt intake; and cultural anthropologists, unable to provide human groups experimentally with varying resource abundances for many centuries, still study long-term effects of resource abundance on human societies by comparing recent Polynesian populations living on islands differing naturally in resource abundance.

The student of human history can draw on many more natural experiments than just comparisons among the five inhabited continents. Comparisons can also utilize large islands that have developed complex societies in a considerable degree of isolation (such as Japan, Madagascar, Native American Hispaniola, New Guinea, Hawaii, and many others), as well as societies on hundreds of smaller islands and regional societies within each of the continents. Natural experiments in any field, whether in ecology or human history, are inherently open to potential methodological criticisms. Those include confounding effects of natural variation in additional variables besides the one of interest, as well as problems in inferring chains of causation from observed correlations between variables. Such methodological problems have been discussed in great detail for some of the historical sciences. In particular, epidemiology, the science of drawing inferences about human diseases by comparing groups of people (often by retrospective historical studies), has for a long time successfully employed formalized procedures for dealing with problems similar to those facing historians of human societies. In short, I acknowledge that it is much more difficult to understand human history than to understand problems in fields of science where history is unimportant and where fewer individual variables operate. Nevertheless, successful methodologies for analyzing historical problems have been worked out in several fields. As a result, the histories of dinosaurs, nebulae, and glaciers are generally acknowledged to belong to fields of science rather than to the humanities.

The difficulties historians face in establishing cause-and-effect relations in the history of human societies are broadly similar to the difficulties facing astronomers, climatologists, ecologists, evolutionary biologists, geologists, and palaeontologists. To varying degrees each of these fields is plagued by the impossibility of performing replicated, controlled experimental interventions, the complexity arising from enormous numbers of variables, the resulting uniqueness of each system, the consequent impossibility of formulating universal laws, and the difficulties of predicting emergent properties and future behaviour. Prediction in history, as in other historical sciences, is most feasible on large spatial scales and over long times, when the unique features of millions of small-scale brief events become averaged out. Just as I could predict the sex ratio of the next 1,000 newborns but not the sexes of my own two children, the historian can recognize factors that made2 1 inevitable the broad outcome of the collision between American and Eurasian societies after 13,000 years of separate developments, but not the outcome of the 1960 U.S. presidential election. The details of which candidate said what during a single televised debate in October 1960 Could have given the electoral victory to Nixon instead of to Kennedy, but no details of who said what could have blocked the European conquest of Native Americans. How can students of human history profit from the experience of scientists in other historical sciences? A methodology that has proved useful involves the comparative method and so-called natural experiments. While neither astronomers studying galaxy formation nor human historians can manipulate their systems in controlled laboratory experiments, they both can take advantage of natural experiments, by comparing systems differing in the presence or absence (or in the strong or weak effect) of some putative causative factor. For example, epidemiologists, forbidden to feed large amounts of salt to people experimentally, have still been able to identify effects of high salt intake by comparing groups of humans who already differ greatly in their salt intake; and cultural anthropologists, unable to provide human groups experimentally with varying resource abundances for many centuries, still study long-term effects of resource abundance on human societies by comparing recent Polynesian populations living on islands differing naturally in resource abundance.

The student of human history can draw on many more natural experiments than just comparisons among the five inhabited continents. Comparisons can also utilize large islands that have developed complex societies in a considerable degree of isolation (such as Japan, Madagascar, Native American Hispaniola, New Guinea, Hawaii, and many others), as well as societies on hundreds of smaller islands and regional societies within each of the continents. Natural experiments in any field, whether in ecology or human history, are inherently open to potential methodological criticisms. Those include confounding effects of natural variation in additional variables besides the one of interest, as well as problems in inferring chains of causation from observed correlations between variables. Such methodological problems have been discussed in great detail for some of the historical sciences. In particular, epidemiology, the science of drawing inferences about human diseases by comparing groups of people (often by retrospective historical studies), has for a long time successfully employed formalized procedures for dealing with problems similar to those facing historians of human societies. In short, I acknowledge that it is much more difficult to understand human history than to understand problems in fields of science where history is unimportant and where fewer individual variables operate. Nevertheless, successful methodologies for analyzing historical problems have been worked out in several fields. As a result, the histories of dinosaurs, nebulae, and glaciers are generally acknowledged to belong to fields of science rather than to the humanities.

In each question, there are five sentences/paragraphs. The sentence/ paragraph labelled A is in its correct place. The four that follow are labelled B, C, D and E, and need to be arranged in the logical order to form a coherent paragraph/passage. From the given options, choose the most appropriate option.

In each question, there are five sentences/paragraphs. The sentence/ paragraph labelled A is in its correct place. The four that follow are labelled B, C, D and E, and need to be arranged in the logical order to form a coherent paragraph/passage. From the given options, choose the most appropriate option.

In each question, there are five sentences/paragraphs. The sentence/ paragraph labelled A is in its correct place. The four that follow are labelled B, C, D and E, and need to be arranged in the logical order to form a coherent paragraph/passage. From the given options, choose the most appropriate option.

In each question, there are five sentences/paragraphs. The sentence/ paragraph labelled A is in its correct place. The four that follow are labelled B, C, D and E, and need to be arranged in the logical order to form a coherent paragraph/passage. From the given options, choose the most appropriate option.

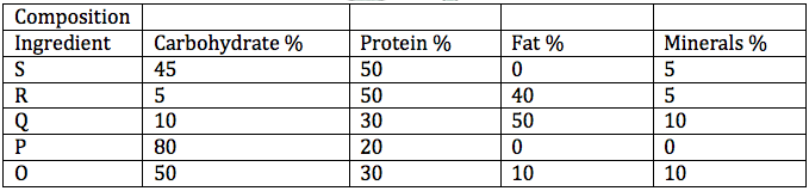

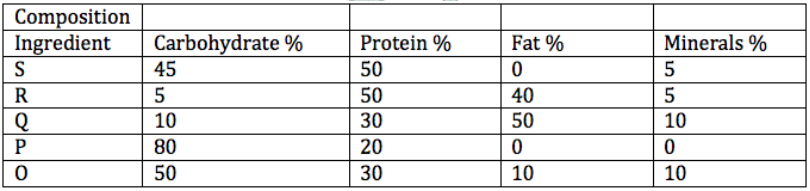

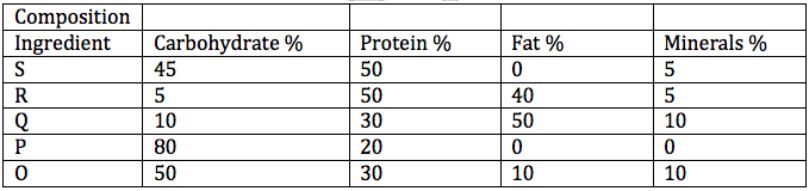

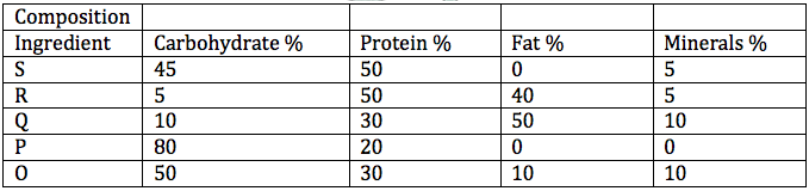

A health-drink company’s R&D department is trying to make various diet formulations, which can be used for certain specific purposes. It is considering a choice of 5 alternative ingredients (O, P, Q, R, and S), which can be used in different proportions in the formulations.

The table below gives the composition of these ingredients. The cost per unit of each of these ingredients is O: 150, P: 50, Q: 200, R: 500, S: 100.

A health-drink company’s R&D department is trying to make various diet formulations, which can be used for certain specific purposes. It is considering a choice of 5 alternative ingredients (O, P, Q, R, and S), which can be used in different proportions in the formulations.

The table below gives the composition of these ingredients. The cost per unit of each of these ingredients is O: 150, P: 50, Q: 200, R: 500, S: 100.

A health-drink company’s R&D department is trying to make various diet formulations, which can be used for certain specific purposes. It is considering a choice of 5 alternative ingredients (O, P, Q, R, and S), which can be used in different proportions in the formulations.

The table below gives the composition of these ingredients. The cost per unit of each of these ingredients is O: 150, P: 50, Q: 200, R: 500, S: 100.

A health-drink company’s R&D department is trying to make various diet formulations, which can be used for certain specific purposes. It is considering a choice of 5 alternative ingredients (O, P, Q, R, and S), which can be used in different proportions in the formulations.

The table below gives the composition of these ingredients. The cost per unit of each of these ingredients is O: 150, P: 50, Q: 200, R: 500, S: 100.

Each question is followed by two statements, A and B. Answer each question using the following instructions:

Each question is followed by two statements, A and B. Answer each question using the following instructions:

Each question is followed by two statements, A and B. Answer each question using the following instructions:

Each question is followed by two statements, A and B. Answer each question using the following instructions:

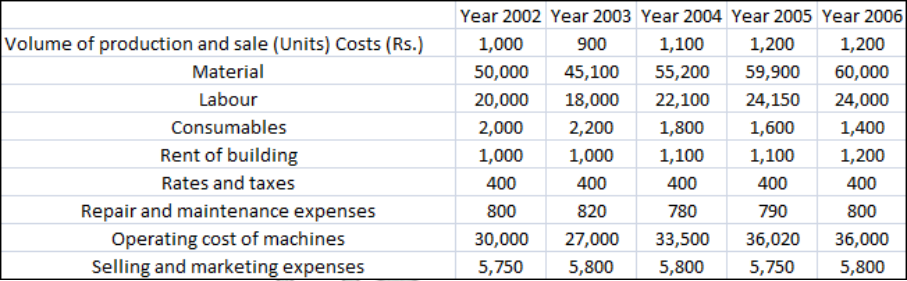

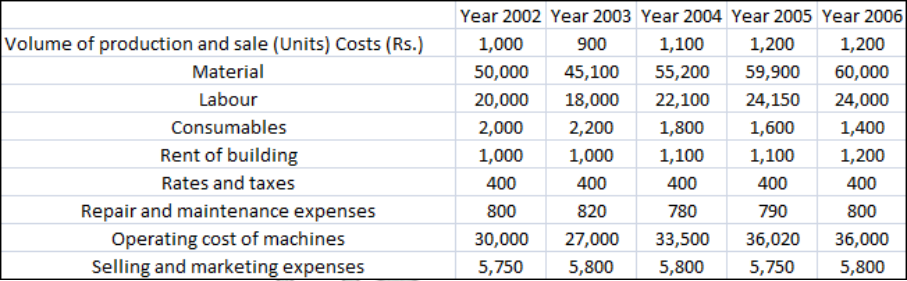

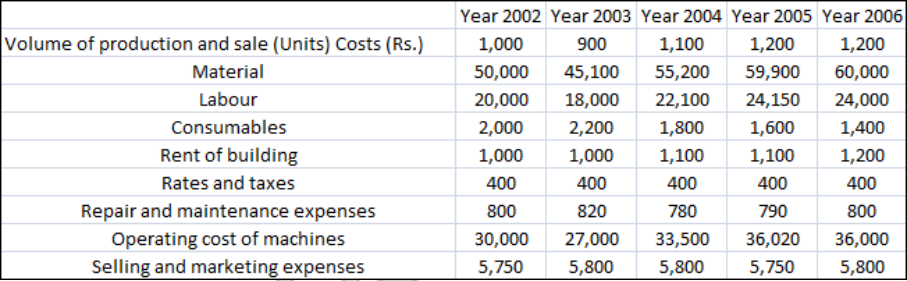

The following table shows the break-up of actual costs incurred by a company in last five years (year 2002 to year 2006) to produce a particular product.

The production capacity of the company is 2000 units. The selling price for the year 2006 was Rs. 125 per unit. Some costs change almost in direct proportion to the change in volume of production, while others do not follow any obvious pattern of change with respect to the volume of production and hence are considered fixed. Using the information provided for the year 2006 as the basis for projecting the figures for the year 2007, answer the following questions:

The following table shows the break-up of actual costs incurred by a company in last five years (year 2002 to year 2006) to produce a particular product.

The production capacity of the company is 2000 units. The selling price for the year 2006 was Rs. 125 per unit. Some costs change almost in direct proportion to the change in volume of production, while others do not follow any obvious pattern of change with respect to the volume of production and hence are considered fixed. Using the information provided for the year 2006 as the basis for projecting the figures for the year 2007, answer the following questions:

The following table shows the break-up of actual costs incurred by a company in last five years (year 2002 to year 2006) to produce a particular product.

The production capacity of the company is 2000 units. The selling price for the year 2006 was Rs. 125 per unit. Some costs change almost in direct proportion to the change in volume of production, while others do not follow any obvious pattern of change with respect to the volume of production and hence are considered fixed. Using the information provided for the year 2006 as the basis for projecting the figures for the year 2007, answer the following questions:

The following table shows the break-up of actual costs incurred by a company in last five years (year 2002 to year 2006) to produce a particular product.

The production capacity of the company is 2000 units. The selling price for the year 2006 was Rs. 125 per unit. Some costs change almost in direct proportion to the change in volume of production, while others do not follow any obvious pattern of change with respect to the volume of production and hence are considered fixed. Using the information provided for the year 2006 as the basis for projecting the figures for the year 2007, answer the following questions:

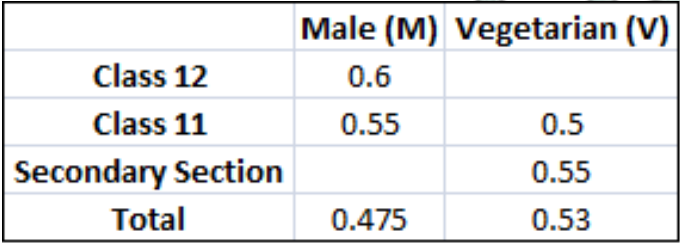

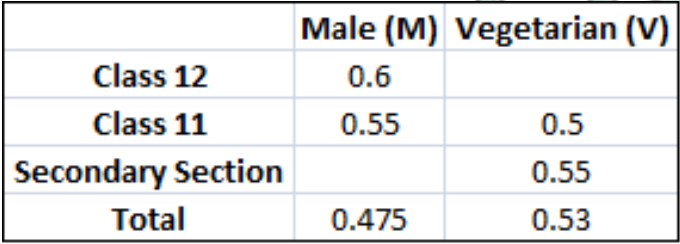

The proportion of male students and the proportion of vegetarian students in a school are given below. The school has a total of 800 students, 80% of whom are in the Secondary Section and rest equally divided between Class 11 and 12.

The proportion of male students and the proportion of vegetarian students in a school are given below. The school has a total of 800 students, 80% of whom are in the Secondary Section and rest equally divided between Class 11 and 12.

The proportion of male students and the proportion of vegetarian students in a school are given below. The school has a total of 800 students, 80% of whom are in the Secondary Section and rest equally divided between Class 11 and 12.

The proportion of male students and the proportion of vegetarian students in a school are given below. The school has a total of 800 students, 80% of whom are in the Secondary Section and rest equally divided between Class 11 and 12.

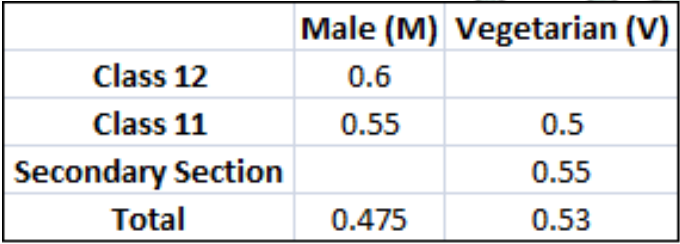

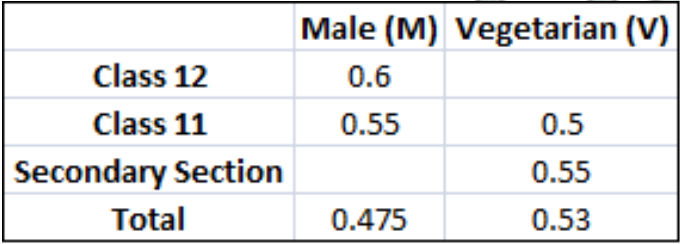

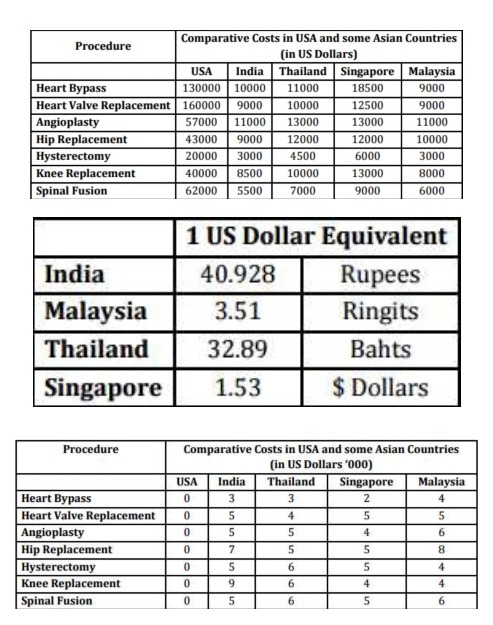

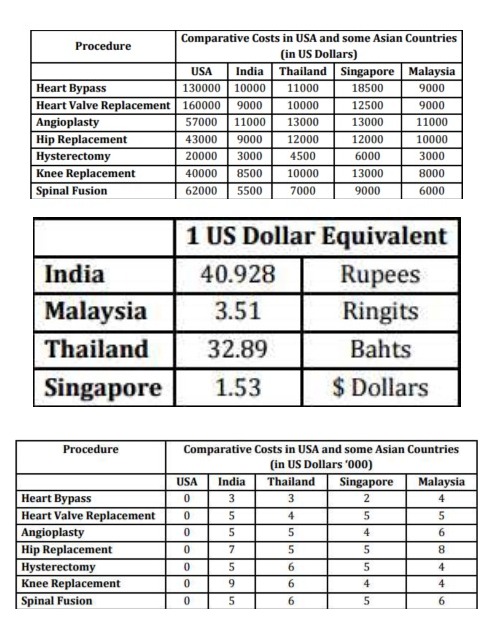

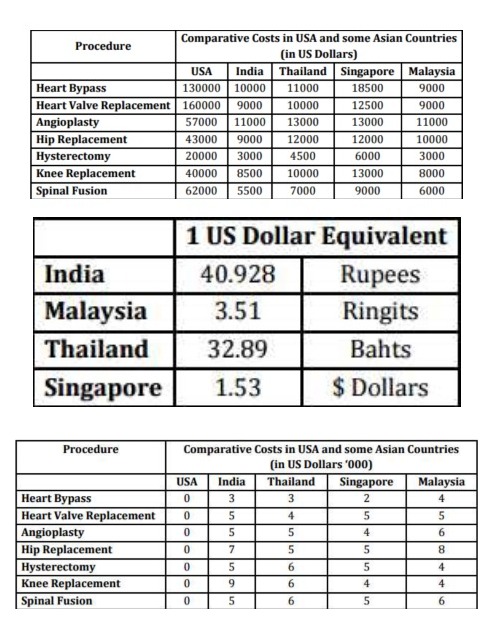

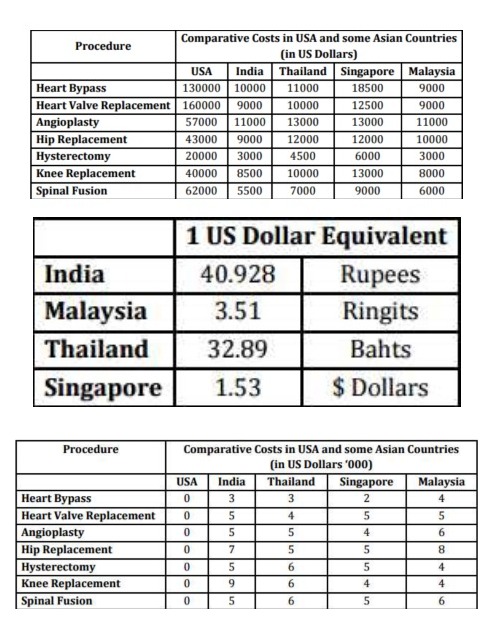

The Table I shows the comparative costs, in US Dollars, of major surgeries in USA and a select few Asian countries.

The equivalent of US Dollar in the local currencies is given in Table II

A consulting firm found that the quality of the health services were not the same in all the countries above. A poor quality of a surgery may have significant repercussions in future, resulting in more cost in correcting mistakes. The cost of poor quality of surgery is given in Table III

The Table I shows the comparative costs, in US Dollars, of major surgeries in USA and a select few Asian countries.

The equivalent of US Dollar in the local currencies is given in Table II

A consulting firm found that the quality of the health services were not the same in all the countries above. A poor quality of a surgery may have significant repercussions in future, resulting in more cost in correcting mistakes. The cost of poor quality of surgery is given in Table III

The Table I shows the comparative costs, in US Dollars, of major surgeries in USA and a select few Asian countries.

The equivalent of US Dollar in the local currencies is given in Table II

A consulting firm found that the quality of the health services were not the same in all the countries above. A poor quality of a surgery may have significant repercussions in future, resulting in more cost in correcting mistakes. The cost of poor quality of surgery is given in Table III

The Table I shows the comparative costs, in US Dollars, of major surgeries in USA and a select few Asian countries.

The equivalent of US Dollar in the local currencies is given in Table II

A consulting firm found that the quality of the health services were not the same in all the countries above. A poor quality of a surgery may have significant repercussions in future, resulting in more cost in correcting mistakes. The cost of poor quality of surgery is given in Table III

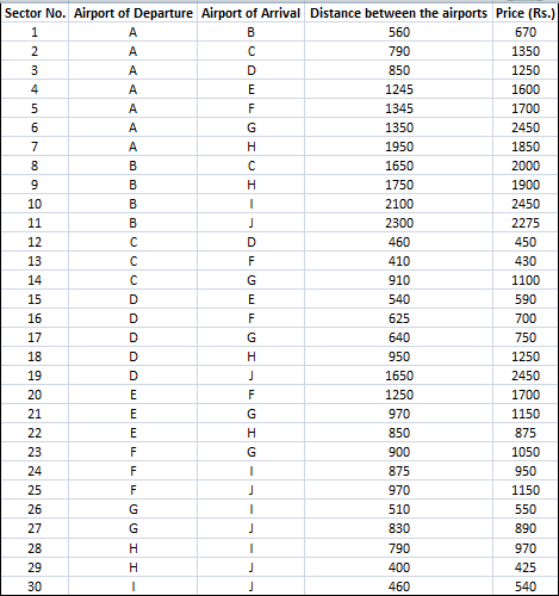

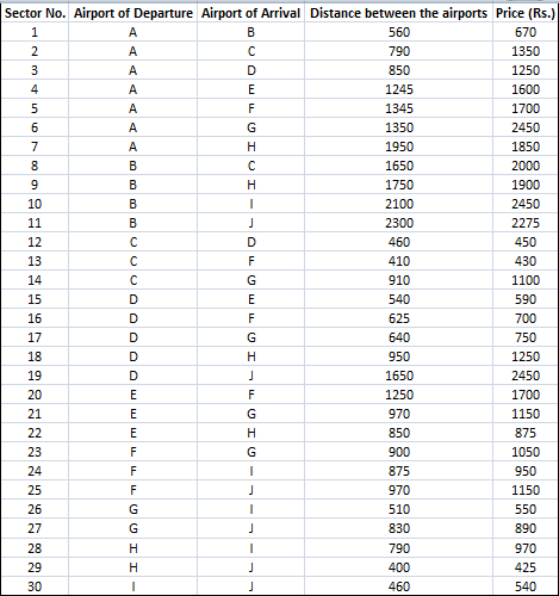

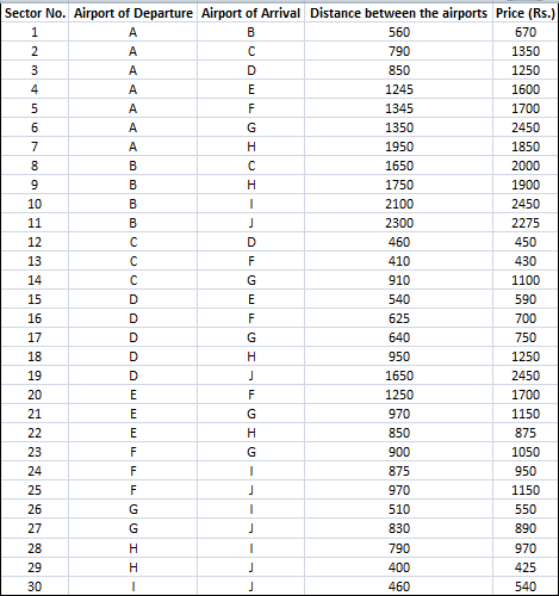

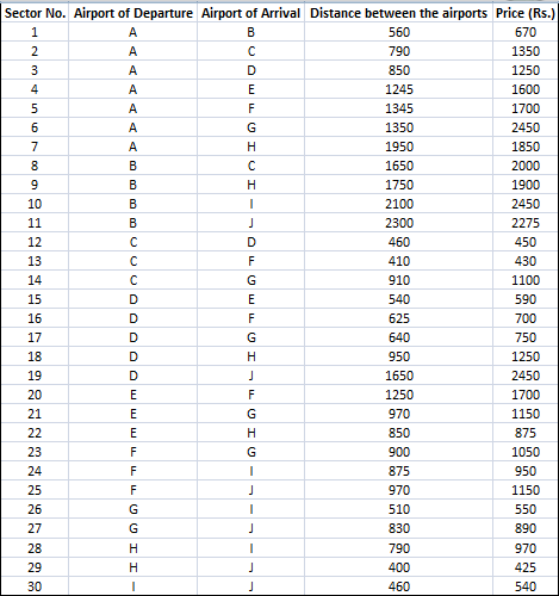

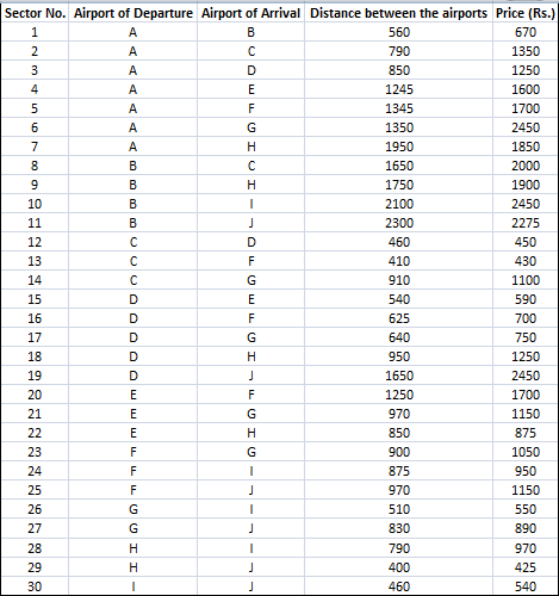

A low-cost airline company connects ten India cities, A to J. The table below gives the distance between a pair of airports and the corresponding price charged by the company. Travel is permitted only from a departure airport to an arrival airport. The customers do not travel by a route where they have to stop at more than two intermediate airports.

A low-cost airline company connects ten India cities, A to J. The table below gives the distance between a pair of airports and the corresponding price charged by the company. Travel is permitted only from a departure airport to an arrival airport. The customers do not travel by a route where they have to stop at more than two intermediate airports.

A low-cost airline company connects ten India cities, A to J. The table below gives the distance between a pair of airports and the corresponding price charged by the company. Travel is permitted only from a departure airport to an arrival airport. The customers do not travel by a route where they have to stop at more than two intermediate airports.

A low-cost airline company connects ten India cities, A to J. The table below gives the distance between a pair of airports and the corresponding price charged by the company. Travel is permitted only from a departure airport to an arrival airport. The customers do not travel by a route where they have to stop at more than two intermediate airports.

A low-cost airline company connects ten India cities, A to J. The table below gives the distance between a pair of airports and the corresponding price charged by the company. Travel is permitted only from a departure airport to an arrival airport. The customers do not travel by a route where they have to stop at more than two intermediate airports.

Each question is followed by two statements A and B. Indicate your responses based on data sufficiency

Each question is followed by two statements A and B. Indicate your responses based on data sufficiency

Each question is followed by two statements A and B. Indicate your responses based on data sufficiency

Each question is followed by two statements A and B. Indicate your responses based on data sufficiency

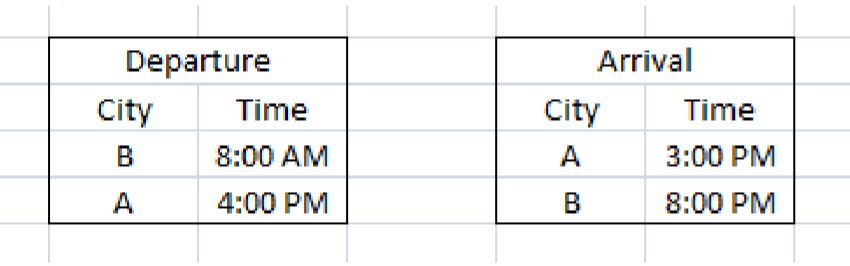

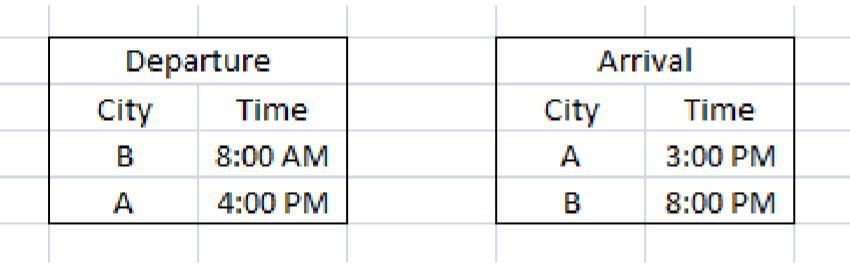

Directions for the following two questions: Cities A and B are in different time zones. A is located 3000 km east of B. The table below describes the schedule of an airline operating non-stop flights between A and B. All the times indicated are local and on the same day.

Assume that planes cruise at the same speed in both directions. However, the effective speed is influenced by a steady wind blowing from east to west at 50 km per hour.

Directions for the following two questions: Cities A and B are in different time zones. A is located 3000 km east of B. The table below describes the schedule of an airline operating non-stop flights between A and B. All the times indicated are local and on the same day.

Assume that planes cruise at the same speed in both directions. However, the effective speed is influenced by a steady wind blowing from east to west at 50 km per hour.

Directions for the following two questions: Shabnam is considering three alternatives to invest her surplus cash for a week. She wishes to guarantee maximum returns on her investment. She has three options, each of which can be utilized fully or partially in conjunction with others.

Option A: Invest in a public sector bank. It promises a return of +0.10%.

Option B: Invest in mutual funds of ABC Ltd. A rise in the stock market will result in a return of +5%, while a fall will entail a return of – 3%.

Option C: Invest in mutual funds of CBA Ltd. A rise in the stock market will result in a return of – 2.5%, while a fall will entail a return of + 2%

Directions for the following two questions: Shabnam is considering three alternatives to invest her surplus cash for a week. She wishes to guarantee maximum returns on her investment. She has three options, each of which can be utilized fully or partially in conjunction with others.

Option A: Invest in a public sector bank. It promises a return of +0.10%.

Option B: Invest in mutual funds of ABC Ltd. A rise in the stock market will result in a return of +5%, while a fall will entail a return of – 3%.

Option C: Invest in mutual funds of CBA Ltd. A rise in the stock market will result in a return of – 2.5%, while a fall will entail a return of + 2%

Let S be the set of all pairs (i, j) where 1 <= i < j <= n , and n >= 4 (i and j are natural numbers). Any two distinct members of S are called “friends” if they have one constituent of the pairs in common and “enemies” otherwise.

For example, if n = 4, then S = {(1, 2), (1, 3), (1, 4), (2, 3), (2, 4), (3, 4)}. Here, (1, 2) and (1, 3) are friends, (1,2) and (2, 3) are also friends, but (1,4) and (2, 3) are enemies.

Let S be the set of all pairs (i, j) where 1 <= i < j <= n , and n >= 4 (i and j are natural numbers). Any two distinct members of S are called “friends” if they have one constituent of the pairs in common and “enemies” otherwise.

For example, if n = 4, then S = {(1, 2), (1, 3), (1, 4), (2, 3), (2, 4), (3, 4)}. Here, (1, 2) and (1, 3) are friends, (1,2) and (2, 3) are also friends, but (1,4) and (2, 3) are enemies.

Directions for the following two questions: Mr. David manufactures and sells a single product at a fixed price in a niche market. The selling price of each unit is Rs. 30. On the other hand, the cost, in rupees, of producing x units is , where b and c are some constants. Mr. David noticed that doubling the daily production from 20 to 40 units increases the daily production cost by 66.67%.

However, an increase in daily production from 40 to 60 units results in an increase of only 50% in the daily production cost. Assume that demand is unlimited and that Mr. David can sell as much as he can produce. His objective is to maximize the profit.

Directions for the following two questions: Mr. David manufactures and sells a single product at a fixed price in a niche market. The selling price of each unit is Rs. 30. On the other hand, the cost, in rupees, of producing x units is , where b and c are some constants. Mr. David noticed that doubling the daily production from 20 to 40 units increases the daily production cost by 66.67%.

However, an increase in daily production from 40 to 60 units results in an increase of only 50% in the daily production cost. Assume that demand is unlimited and that Mr. David can sell as much as he can produce. His objective is to maximize the profit.

Let a1 = p and b1 = q , where p and q are positive quantities.

Define an = pbn-1 , bn = qbn-1 for even n > 1. and an = pan-1 , bn = qan-1 for odd n > 1.

Let a1 = p and b1 = q , where p and q are positive quantities.

Define an = pbn-1 , bn = qbn-1 for even n > 1. and an = pan-1 , bn = qan-1 for odd n > 1.

Answer each question individually.

Answer each question individually.

Answer each question individually.

Answer each question individually.

Answer each question individually.

Answer each question individually.

Answer each question individually.

Answer each question individually.

Answer each question individually.

Answer each question individually.

Answer each question individually.

icon to zoom in and click on

icon to zoom in and click on  icon to zoom out of any question.

icon to zoom out of any question.